about marrakech

Marrakesh or Marrakech (/məˈrækɛʃ/ or /ˌmærəˈkɛʃ/;[3] Arabic: مراكش, romanized: murrākuš, pronounced [murraːkuʃ]; Berber languages: ⵎⵕⵕⴰⴽⵛ, romanized: mṛṛakc[4]) is the fourth largest city in the Kingdom of Morocco.[2] It is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakesh-Safi region. The city is situated west of the foothills of the Atlas Mountains. Marrakesh is 580 km (360 mi) southwest of Tangier, 327 km (203 mi) southwest of the Moroccan capital of Rabat, 239 km (149 mi) south of Casablanca, and 246 km (153 mi) northeast of Agadir.

The region has been inhabited by Berber farmers since Neolithic times. The city was founded in 1070 by Emir Abu Bakr ibn Umar as the imperial capital of the Almoravid Empire. The Almoravids established the first major structures in the city and shaped its layout for centuries to come. The red walls of the city, built by Ali ibn Yusuf in 1122–1123, and various buildings constructed in red sandstone afterwards, have given the city the nickname of the “Red City” (المدينة الحمراء Almadinat alhamra’) or “Ochre City” (ville ocre). Marrakesh grew rapidly and established itself as a cultural, religious, and trading center for the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa. Jemaa el-Fnaa is the busiest square in Africa.

After a period of decline, the city was surpassed by Fez, and in the early 16th century, Marrakesh again became the capital of the kingdom. The city regained its preeminence under wealthy Saadian sultans Abdallah al-Ghalib and Ahmad al-Mansur, who embellished the city with sumptuous palaces such as the El Badi Palace (1578) and restored many ruined monuments. Beginning in the 17th century, the city became popular among Sufi pilgrims for its seven patron saints who are entombed here. In 1912 the French Protectorate in Morocco was established and T’hami El Glaoui became Pasha of Marrakesh and held this position nearly throughout the protectorate until the role was dissolved upon the independence of Morocco and the reestablishment of the monarchy in 1956.

Marrakesh comprises an old fortified city packed with vendors and their stalls. This medina quarter is a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Today it is one of the busiest cities in Africa and serves as a major economic center and tourist destination. Real estate and hotel development in Marrakesh have grown dramatically in the 21st century. Marrakesh is particularly popular with the French, and numerous French celebrities own property in the city. Marrakesh has the largest traditional market (souk) in Morocco, with some 18 souks selling wares ranging from traditional Berber carpets to modern consumer electronics. Crafts employ a significant percentage of the population, who primarily sell their products to tourists.

Marrakesh is served by Ménara International Airport and by Marrakesh railway station, which connects the city to Casablanca and northern Morocco. Marrakesh has several universities and schools, including Cadi Ayyad University. A number of Moroccan football clubs are here, including Najm de Marrakech, KAC Marrakech, Mouloudia de Marrakech and Chez Ali Club de Marrakech. The Marrakesh Street Circuit hosts the World Touring Car Championship, Auto GP and FIA Formula Two Championship races.

Etymology[edit]

The exact meaning of the name is debated.[5] One possible origin of the name Marrakesh is from the Berber (Amazigh) words amur (n) akush (ⴰⵎⵓⵔ ⵏ ⴰⴽⵓⵛ), which means “Land of God”.[4] According to historian Susan Searight, however, the town’s name was first documented in an 11th-century manuscript in the Qarawiyyin library in Fez, where its meaning was given as “country of the sons of Kush”.[6] The word mur [7] is used now in Berber mostly in the feminine form tamurt. The same word “mur” appears in Mauretania, the North African kingdom from antiquity, although the link remains controversial as this name possibly originates from μαύρος mavros, the ancient Greek word for black.[5] The common English spelling is “Marrakesh”,[8][9] although “Marrakech” (the French spelling) is also widely used.[4] The name is spelled Mṛṛakc in the Berber Latin alphabet, Marraquexe in Portuguese, Marrakech in Spanish.[10] A typical pronunciation in Moroccan Arabic is marrākesh with stress on the second syllable, while vowels in the other syllables may be barely pronounced.

From medieval times until around the beginning of the 20th century, the entire country of Morocco was known as the “Kingdom of Marrakesh”, as the kingdom’s historic capital city was often Marrakesh.[11][12] The name for Morocco is still “Marrakesh” (مراكش) to this day in Persian and Urdu as well as many other South Asian languages. Various European names for Morocco (Marruecos, Marrocos, Maroc, Marokko, etc.) are directly derived from the Berber word Murakush. Conversely, the city itself was in earlier times simply called Marocco City (or similar) by travelers from abroad. The name of the city and the country diverged after the Treaty of Fez divided Morocco into a French protectorate in Morocco and Spanish protectorate in Morocco, and the old interchangeable usage lasted widely until about the interregnum of Mohammed Ben Aarafa (1953–1955).[13] The latter episode set in motion the country’s return to independence, when Morocco officially became المملكة المغربية (al-Mamlaka al-Maġribiyya, “The Maghreb Kingdom”), its name no longer referring to the city of Marrakesh. Marrakesh is known by a variety of nicknames, including the “Red City”, the “Ochre City” and “the Daughter of the Desert”, and has been the focus of poetic analogies such as one comparing the city to “a drum that beats an African identity into the complex soul of Morocco.”[14]

History[edit]

The Marrakesh area was inhabited by Berber farmers from Neolithic times, and numerous stone implements have been unearthed in the area.[6] Marrakesh was founded by Abu Bakr ibn Umar, chieftain and second cousin of the Almoravid king Yusuf ibn Tashfin (c. 1061–1106).[15][16] Historical sources cite a variety of dates for this event ranging between 1062 (454 in the Hijri calendar), according to Ibn Abi Zar and Ibn Khaldun, and 1078 (470 AH), according to Muhammad al-Idrisi.[17] The date most commonly used by modern historians is 1070,[18] although 1062 is still cited by some writers.[19] The Almoravids, a Berber dynasty seeking to reform Islamic society, ruled an emirate stretching from the edge of Senegal to the centre of Spain and from the Atlantic coast to Algiers.[20] They used Marrakesh as their capital and established its first structures, including mosques and a fortified residence, the Ksar al-Hajjar, near the present-day Kutubiyya Mosque.[21] These Almoravid foundations also influenced the layout and urban organization of the city for centuries to come. For example, the present-day Jemaa el-Fnaa originated from a public square in front of the Almoravid palace gates, the Rahbat al-Ksar,[22][23] and the major souks (markets) of the city developed roughly in the area between this square and the city’s main mosque, where they remain today.[24] The city developed the community into a trading centre for the Maghreb and sub-Saharan Africa.[25] It grew rapidly and established itself as a cultural and religious centre, supplanting Aghmat, which had long been the capital of Haouz. Andalusi craftsmen from Cordoba and Seville built and decorated numerous monuments, importing the Cordoban Umayyad style characterised by carved domes and cusped arches.[6][26] This Andalusian influence merged with designs from the Sahara and West Africa, creating a unique style of architecture which was fully adapted to the Marrakesh environment. Yusuf ibn Tashfin built houses, minted coins, and brought gold and silver to the city in caravans.[6] His son and successor, Ali Ibn Yusuf, built the Ben Youssef Mosque, the city’s main mosque, between 1120 and 1132.[27][28] He also fortified the city with city walls for the first time in 1126–1127 and expanded its water supply by creating the underground water system known as the khettara.[29][30]

Gold Almoravid dinar minted during the reign of Ali ibn Yusef.

In 1125, the preacher Ibn Tumart settled in Tin Mal in the mountains to the south of Marrakesh, founding the Almohad movement. This new faction, composed mainly of Masmuda tribesmen, followed a doctrine of radical reform with Ibn Tumart as the mahdi, a messianic figure. He preached against the Almoravids and influenced a revolt which succeeded in bringing about the fall of nearby Aghmat, but stopped short of bringing down Marrakesh following an unsuccessful siege in 1130.[6] Ibn Tumart died shortly after in the same year, but his successor Abd al-Mu’min took over the political leadership of the movement and captured Marrakesh in 1147 after a siege of several months.[31] The Almohads purged the Almoravid population over three days and established the city as their new capital.[32] They went on to take over much of the Almoravids’ former territory in Africa and the Iberian Peninsula. In 1147, shortly after the city’s conquest, Abd al-Mu’min founded the Kutubiyya Mosque (or Koutoubia Mosque), next to the former Almoravid palace, to serve as the city’s new main mosque.[33] The Almoravid mosques were either demolished or abandoned as the Almohads enacted their religious reforms.[32] Abd al-Mu’min was also responsible for establishing the Menara Gardens in 1157, while his successor Abu Ya’qub Yusuf (r. 1163–1184) began the Agdal Gardens.[34][35] Ya’qub al-Mansur (r. 1184–1199), possibly on the orders of his father Abu Ya’qub Yusuf, was responsible for building the Kasbah, a citadel and palace district on the south side of the city.[36][37] The Kasbah housed the center of government and the residence of the caliph, a title borne by the Almohad rulers to rival the eastern Abbasid Caliphate. In part because of these various additions, the Almohads also improved the water supply system and created water reservoirs to irrigate their gardens.[38] Thanks to its economic, political, and cultural importance, Marrakesh hosted many writers, artists, and intellectuals, many of them from Al-Andalus, including the famous philosopher Averroes of Cordoba.[39][40]

Detail of the Cantiga de Santa Maria #181. The cantiga #181 depicts the successful 1261–62 defence of Marrakesh by Almohad ruler Al-Murtada (with help from Christian militias) from the siege laid on by Marinid ruler Abu Yusuf.[41]

The death of Yusuf II in 1224 began a period of instability. Marrakesh became the stronghold of the Almohad tribal sheikhs and the ahl ad-dar (descendants of Ibn Tumart), who sought to claw power back from the ruling Almohad family. Marrakesh was taken, lost and retaken by force multiple times by a stream of caliphs and pretenders, such as during the brutal seizure of Marrakesh by the Sevillan caliph Abd al-Wahid II al-Ma’mun in 1226, which was followed by a massacre of the Almohad tribal sheikhs and their families and a public denunciation of Ibn Tumart’s doctrines by the caliph from the pulpit of the Kasbah Mosque.[42] After al-Ma’mun’s death in 1232, his widow attempted to forcibly install her son, acquiring the support of the Almohad army chiefs and Spanish mercenaries with the promise to hand Marrakesh over to them for the sack. Hearing of the terms, the people of Marrakesh sought to make an agreement with the military captains and saved the city from destruction with a sizable payoff of 500,000 dinars.[42] In 1269, Marrakesh was conquered by nomadic Zenata tribes who overran the last of the Almohads.[43] The city then fell into a state of decline, which soon led to the loss of its status as capital to rival city Fez.

In the early 16th century, Marrakesh again became the capital of Morocco, after a period when it was the seat of the Hintata emirs. It quickly reestablished its status, especially during the reigns of the Saadian sultans Abdallah al-Ghalib and Ahmad al-Mansur.[44][45] Thanks to the wealth amassed by the Sultans, Marrakesh was embellished with sumptuous palaces while its ruined monuments were restored. El Badi Palace, begun by Ahmad al-Mansur in 1578, was made with costly materials including marble from Italy.[46][47] The palace was intended primarily for hosting lavish receptions for ambassadors from Spain, England, and the Ottoman Empire, showcasing Saadian Morocco as a nation whose power and influence reached as far as the borders of Niger and Mali.[48] Under the Saadian dynasty, Marrakesh regained its former position as a point of contact for caravan routes from the Maghreb, the Mediterranean and sub-Saharan Africa.

For centuries Marrakesh has been known as the location of the tombs of Morocco’s seven patron saints (sebaatou rizjel). When sufism was at the height of its popularity during the late 17th-century reign of Moulay Ismail, the festival of these saints was founded by Abu Ali al-Hassan al-Yusi at the request of the sultan.[49] The tombs of several renowned figures were moved to Marrakesh to attract pilgrims, and the pilgrimage associated with the seven saints is now a firmly established institution. Pilgrims visit the tombs of the saints in a specific order, as follows: Sidi Yusuf Ali Sanhaji (1196–97), a leper; Qadi Iyyad or qadi of Ceuta (1083–1149), a theologian and author of Ash-Shifa (treatises on the virtues of Muhammad); Sidi Bel Abbas (1130–1204), known as the patron saint of the city and most revered in the region; Sidi Muhammad al-Jazuli (1465), a well known Sufi who founded the Jazuli brotherhood; Abdelaziz al-Tebaa (1508), a student of al-Jazuli; Abdallah al-Ghazwani (1528), known as Moulay al-Ksour; and Sidi Abu al-Qasim Al-Suhayli, (1185), also known as Imam al-Suhayli.[50][51] Until 1867, European Christians were not authorized to enter the city unless they acquired special permission from the sultan; east European Jews were permitted.[12]

During the early 20th century, Marrakesh underwent several years of unrest. After the premature death in 1900 of the grand vizier Ba Ahmed, who had been designated regent until the designated sultan Abd al-Aziz became of age, the country was plagued by anarchy, tribal revolts, the plotting of feudal lords, and European intrigues. In 1907, Marrakesh caliph Moulay Abd al-Hafid was proclaimed sultan by the powerful tribes of the High Atlas and by Ulama scholars who denied the legitimacy of his brother, Abd al-Aziz.[52] It was also in 1907 that Dr. Mauchamp, a French doctor, was murdered in Marrakesh, suspected of spying for his country.[53] France used the event as a pretext for sending its troops from the eastern Moroccan town of Oujda to the major metropolitan center of Casablanca in the west. The French colonial army encountered strong resistance from Ahmed al-Hiba, a son of Sheikh Ma al-‘Aynayn, who arrived from the Sahara accompanied by his nomadic Reguibat tribal warriors. On 30 March 1912, the French Protectorate in Morocco was established.[54] After the Battle of Sidi Bou Othman, which saw the victory of the French Mangin column over the al-Hiba forces in September 1912, the French seized Marrakesh. The conquest was facilitated by the rallying of the Imzwarn tribes and their leaders from the powerful Glaoui family, leading to a massacre of Marrakesh citizens in the resulting turmoil.[55]

T’hami El Glaoui, Pasha of Marrakesh (1912 to 1956).

T’hami El Glaoui, known as “Lord of the Atlas”, became Pasha of Marrakesh, a post he held virtually throughout the 44-year duration of the Protectorate (1912–1956).[56] Glaoui dominated the city and became famous for his collaboration with the general residence authorities, culminating in a plot to dethrone Mohammed Ben Youssef (Mohammed V) and replace him with the Sultan’s cousin, Ben Arafa.[56] Glaoui, already known for his amorous adventures and lavish lifestyle, became a symbol of Morocco’s colonial order. He could not, however, subdue the rise of nationalist sentiment, nor the hostility of a growing proportion of the inhabitants. Nor could he resist pressure from France, who agreed to terminate its Moroccan Protectorate in 1956 due to the launch of the Algerian War (1954–1962) immediately following the end of the war in Indochina (1946–1954), in which Moroccans had been conscripted to fight in Vietnam on behalf of the French Army. After two successive exiles to Corsica and Madagascar, Mohammed Ben Youssef was allowed to return to Morocco in November 1955, bringing an end to the despotic rule of Glaoui over Marrakesh and the surrounding region. A protocol giving independence to Morocco was then signed on 2 March 1956 between French Foreign Minister Christian Pineau and M’Barek Ben Bakkai.[57]

Since the independence of Morocco, Marrakesh has thrived as a tourist destination. In the 1960s and early 1970s, the city became a trendy “hippie mecca”. It attracted numerous western rock stars and musicians, artists, film directors and actors, models, and fashion divas,[58] leading tourism revenues to double in Morocco between 1965 and 1970.[59] Yves Saint Laurent, The Beatles, The Rolling Stones and Jean-Paul Getty all spent significant time in the city; Laurent bought a property here and renovated the Majorelle Gardens.[60][61] Expatriates, especially those from France, have invested heavily in Marrakesh since the 1960s and developed many of the riads and palaces.[60] Old buildings were renovated in the Old Medina, new residences and commuter villages were built in the suburbs, and new hotels began to spring up.

United Nations agencies became active in Marrakesh beginning in the 1970s, and the city’s international political presence has subsequently grown. In 1985, UNESCO declared the old town area of Marrakesh a UNESCO World Heritage Site, raising international awareness of the cultural heritage of the city.[62] In the 1980s, Patrick Guerand-Hermes purchased the 30 acres (12 ha) Ain el Quassimou, built by the family of Leo Tolstoy. [61] On 15 April 1994, the Marrakesh Agreement was signed here to establish the World Trade Organisation,[63] and in March 1997 Marrakesh served as the site of the World Water Council‘s first World Water Forum, which was attended by over 500 international participants.[64]

In the 21st century, property and real estate development in the city has boomed, with a dramatic increase in new hotels and shopping centres, fuelled by the policies of Mohammed VI of Morocco, who aims to increase the number of tourists annually visiting Morocco to 20 million by 2020. In 2010, a major gas explosion occurred in the city. On 28 April 2011, a bomb attack took place in the Jemaa el-Fnaa square, killing 15 people, mainly foreigners. The blast destroyed the nearby Argana Cafe.[65] Police sources arrested three suspects and claimed the chief suspect was loyal to Al-Qaeda, although Al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb denied involvement.[66] In November 2016 the city hosted the 2016 United Nations Climate Change Conference.[67]

Geography[edit]

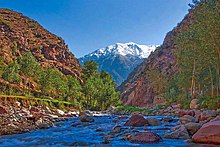

In winter, the Atlas mountains are typically covered in snow and ice.

By road, Marrakesh is 580 kilometres (360 mi) southwest of Tangier, 327 kilometres (203 mi) southwest of the Moroccan capital of Rabat, 239 kilometres (149 mi) southwest of Casablanca, 196 kilometres (122 mi) southwest of Beni Mellal, 177 kilometres (110 mi) east of Essaouira, and 246 kilometres (153 mi) northeast of Agadir.[68] The city has expanded north from the old centre with suburbs such as Daoudiat, Diour El Massakine, Sidi Abbad, Sakar and Amerchich, to the southeast with Sidi Youssef Ben Ali, to the west with Massira and Targa, and southwest to M’hamid beyond the airport.[68] On the P2017 road leading south out of the city are large villages such as Douar Lahna, Touggana, Lagouassem, and Lahebichate, leading eventually through desert to the town of Tahnaout at the edge of the High Atlas, the highest mountainous barrier in North Africa.[68] The average elevation of the snow-covered High Atlas lies above 3,000 metres (9,800 ft). It is mainly composed of Jurassic limestone. The mountain range runs along the Atlantic coast, then rises to the east of Agadir and extends northeast into Algeria before disappearing into Tunisia.[69]

The Ourika River valley

The city is located in the Tensift River valley,[70] with the Tensift River passing along the northern edge of the city. The Ourika River valley is about 30 kilometres (19 mi) south of Marrakesh.[71] The “silvery valley of the Ourika river curving north towards Marrakesh”, and the “red heights of Jebel Yagour still capped with snow” to the south are sights in this area.[72] David Prescott Barrows, who describes Marrakesh as Morocco’s “strangest city”, describes the landscape in the following terms: “The city lies some fifteen or twenty miles [25–30 km] from the foot of the Atlas mountains, which here rise to their grandest proportions. The spectacle of the mountains is superb. Through the clear desert air the eye can follow the rugged contours of the range for great distances to the north and eastward. The winter snows mantle them with white, and the turquoise sky gives a setting for their grey rocks and gleaming caps that is of unrivaled beauty.”[55]

With 130,000 hectares of greenery and over 180,000 palm trees in its Palmeraie, Marrakesh is an oasis of rich plant variety. Throughout the seasons, fragrant orange, fig, pomegranate and olive trees display their color and fruits in Agdal Garden, Menara Garden and other gardens in the city.[73] The city’s gardens feature numerous native plants alongside other species that have been imported over the course of the centuries, including giant bamboos, yuccas, papyrus, palm trees, banana trees, cypress, philodendrons, rose bushes, bougainvilleas, pines and various kinds of cactus plants.

Climate[edit]

A hot semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSh) predominates at Marrakesh. Average temperatures range from 12 °C (54 °F) in the winter to 26–30 °C (79–86 °F) in the summer.[74] The relatively wet winter and dry summer precipitation pattern of Marrakesh mirrors precipitation patterns found in Mediterranean climates. However, the city receives less rain than is typically found in a Mediterranean climate, resulting in a semi-arid climate classification. Between 1961 and 1990 the city averaged 281.3 millimetres (11.1 in) of precipitation annually.[74] Barrows says of the climate, “The region of Marrakesh is frequently described as desert in character, but, to one familiar with the southwestern parts of the United States, the locality does not suggest the desert, rather an area of seasonal rainfall, where moisture moves underground rather than by surface streams, and where low brush takes the place of the forests of more heavily watered regions. The location of Marrakesh on the north side of the Atlas, rather than the south, prevents it from being described as a desert city, and it remains the northern focus of the Saharan lines of communication, and its history, its types of dwellers, and its commerce and arts, are all related to the great south Atlas spaces that reach further into the